Clean cooking for Africa: an urgent priority

Perhaps the most remarkable fact about the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Summit on Clean Cooking for Africa, which was held at UNESCO HQ in Paris on 14 May 2024, is that it happened at all. That’s given the historically low priority afforded by the international community and the media to this topic, especially for Africa’s rapidly growing population. So this event was long overdue, and vitally important.

Women cooking Ugali on a wood-fuel stove in Kenya

The numbers are sobering. Around 80% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s 1.23 billion population, some 980 million people living in 140 million households, still rely on inefficient, polluting, and often unsafe solid fuels and kerosene (paraffin) for their everyday cooking needs. The ‘household air pollution’ (HAP) produced by cooking on ‘dirty’ fuels is responsible for some 700,000 premature deaths from respiratory and circulatory diseases, cancer, adverse birth outcomes, and other conditions we typically associate with tobacco smoking.

These energy use practices also have significant impacts on women’s time, exacerbate deforestation, produce substantial climate warming emissions, hold back development, and entrench gender inequality.

If the transition to clean energy across Sub-Saharan Africa were on track to reach the Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG-7) target to ‘Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for All’ by 2030, then perhaps the IEA Summit would not have been required. But Africa is not on track to reach that goal, and in fact the rate of adoption of clean cooking energy is not keeping pace with population growth.

High-level commitment for a neglected issue

Dr Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the IEA, introducing the Clean Cooking for Africa Summit

Co-chaired by Dr Fatih Birol (IEA Executive Director), Dr Samia Suluhu Hassaan (President of Tanzania), Jonas Gahr Støre (Prime Minister of Norway), and Dr Akinwumi A. Adesina (President of the African Development Bank), the Summit had three broad aims: raising awareness, securing financial commitments, and developing a roadmap of concrete, action-oriented strategies.

The Summit was addressed by four heads of state, more than 20 ministers, the UN Secretary General (via video), WHO Director General (in person), and many other senior officials and representatives of governments, development agencies, civil society, and industry. With this level of commitment and breadth of input, and guided by the three ‘pillars’ of scaling up finance, making clean cooking a policy priority, and catalysing multi-stakeholder partnerships, the Summit held the promise of being a turning point for clean cooking in Africa. So, what were the key messages, and what was achieved?

What are the goals for clean cooking in Africa?

LPG offers the best option for ‘Clean cooking by 2030’, while renewables (including Bio-LPG) are developed to the scale needed to replace fossil fuels by 2050

In his video address to the Summit, UN Secretary General António Guterres emphasised that “reversing the injustices” of lack of access to clean cooking must be a global priority. He stated two goals to aim for:

- Clean Cooking by 2030

- Net Zero by 2050

These goals draw on the UN Energy Report (2023), ‘Achieving Universal Access and Net-Zero Emissions by 2050: A Global Roadmap for Just and Inclusive Clean Cooking Transition’, which additionally includes a 2040 target for all homes to be using ‘Modern Energy Cooking Services’. These are defined as clean fuels, but also include ‘advanced’ biomass stoves that achieve Tier-4 or higher on all six dimensions of the World Bank/ESMAP’s Multi-Tier Framework.

These goals are broadly consistent with pursuing a ‘twin-track’ approach to the development and scaling up of clean cooking energy, as we have recently discussed in The Conversation. This would see investment being put into expanding access to the most widely available and practical clean fuels as rapidly as possible, with a target of reaching SDG-7 by 2030 (primarily LPG), while at the same time growing the scale of renewable options that can displace residual use of fossil-derived fuels over the period up to 2050, including: Bio-LPG, electricity, ethanol, and biogas. Both the IEA scenarios, and the UN Energy Report, see a not insubstantial role for improved biomass cook stoves to 2040, or thereabouts. While some continued use of solid fuel stoves is inevitable during transition, we would like to see greater acknowledgement and discussion of the disparity between performance (especially PM2.5 and CO emissions affecting health) in laboratory testing, compared to what is observed when stoves are in everyday use in homes, and the policy implications of this.

The energy and technology solutions are already available

Clean fuels, including LPG, electricity, ethanol (pictured) and biogas are already available

Several speakers at the Summit, including Dr Birol and Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, emphasised that we already have the energy sources and cooking technologies required to achieve clean cooking for all in Sub-Saharan Africa. The priorities now are the right policies and adequate finance, backed by political will. To quote Dr Birol:

“Solving access to clean cooking does not require a technological breakthrough. It comes down to political will from governments, banks and other entities seeking to eradicate poverty and gender inequality. But today, we are failing women in some of the most vulnerable areas of the world”.

A pay-as-you-go (PAYG) LPG cooking gas system (M-Gas) in Nairobi, Kenya

That is not to say that innovation is not needed. But the priority for new ideas and initiatives does not lie so much with finding new energy sources or cooking technology, but rather with improving the means of delivery and in particular making clean energy affordable for all sectors of African society.

Smart subsidies, ‘pay-as-you-go’, progressive fiscal policy, and making the most of carbon finance, are all areas where innovation can help accelerate access to, and more exclusive use of, clean fuels. I will return to these ideas later in this article.

What do African leaders see as the priorities?

The Presidents of Tanzania, Sierra-Leone and the Togolese Republic, and the Minister of Energy and Petroleum from Kenya, spoke about their countries’ strategies for clean cooking energy. They emphasised the need for a mix of clean solutions, amongst which the contribution from LPG would need to be substantial. The Tanzanian President, Samia Suluhu Hassan, co-chair of the Summit, noted that ‘the key role of gas in a just energy transition needs to be recognised’.

The Presidents of Tanzania, Sierra-Leone and the Togolese Republic, and the Minister of Energy and Petroleum from Kenya, spoke about their countries’ strategies for clean cooking energy. They emphasised the need for a mix of clean solutions, amongst which the contribution from LPG would need to be substantial. The Tanzanian President, Samia Suluhu Hassan, co-chair of the Summit, noted that ‘the key role of gas in a just energy transition needs to be recognised’.

Several speakers reminded delegates about the rapid transitions to LPG for cooking that have been acheived in Indonesia, Brazil, India, and Egypt – evidence that this fuel can deliver ‘scale and speed’. This message is consistent with the clean cooking scenarios presented in recent reports from the IEA, including Africa Energy Outlook (2022) and A Vision for Clean Cooking Access for All (2023) which propose a substantial contribution from LPG, at least over the short to medium-term.

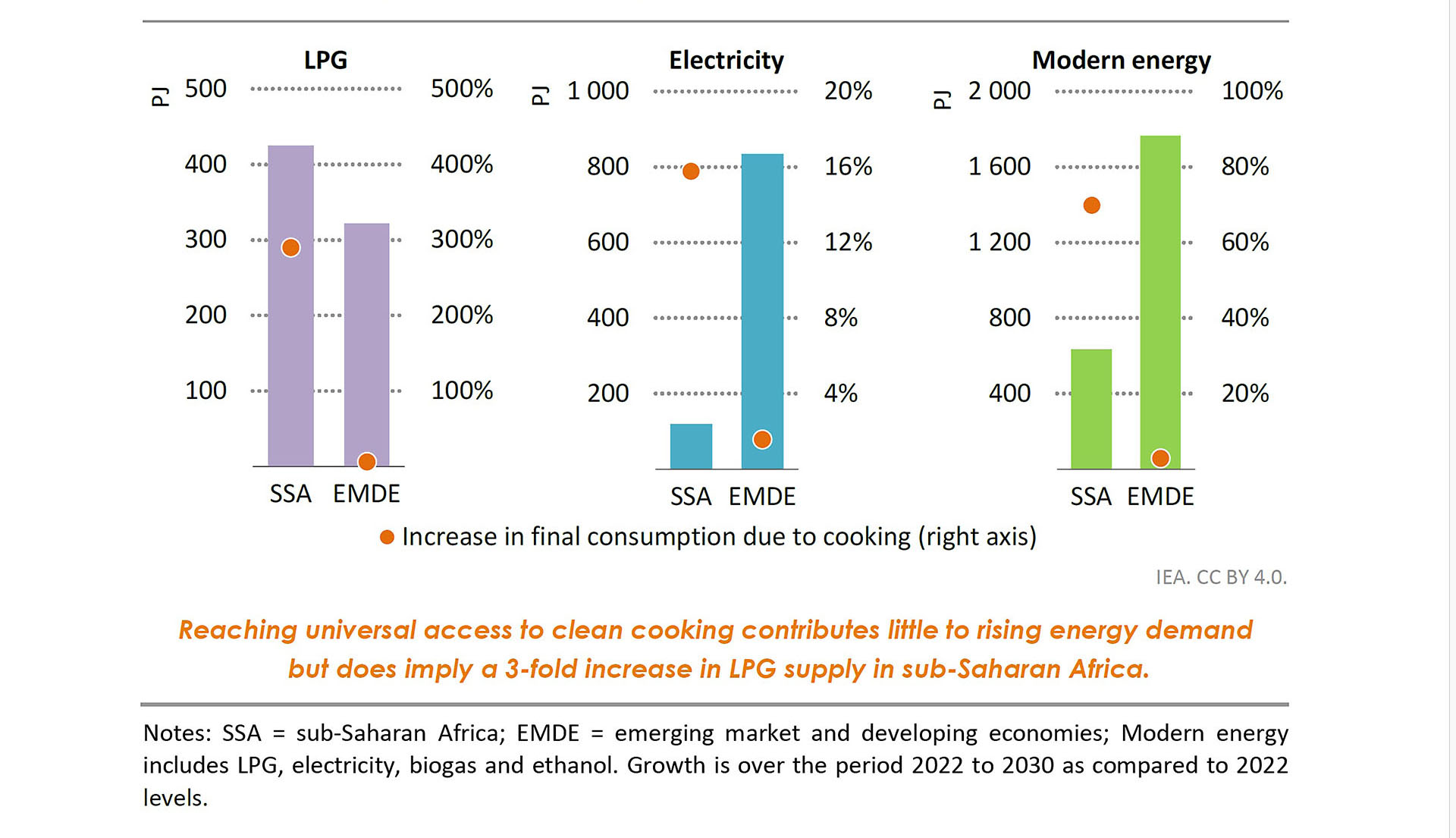

Growth in cooking energy demand by fuel in the Access for All scenario, 2022-2030 (Figure 2.7 in IEA Report ‘A Vision of Clean Cooking Access for All’)

One of the electric pressure cookers being demonstrated in the Summit exhibition area

Electric Cooking (eCooking) was widely discussed and a number of technologies, both electric pressure cookers and induction plates, were demonstrated in the Summit exhibition area. Although the potential of this efficient, clean technology was clearly acknowledged by African leaders, overall there seemed to be more emphasis on eCooking by those promoting this solution. Faure Gnassingbé, President of the Togolese Republic, reported that his country has a target of 70% LPG use in the next few years, and added that eCooking required high quality distribution networks, “and this was a challenge in our country”.

African Development Bank President Dr Akinwumi Adesina reinforced these comments, stating that, “The solutions for clean cooking are well known, from liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), natural gas for use for electricity to allow for electric stoves or eCooking, use of ethanol and biogas. We know of so called improved clean cooking stoves, but they simply give efficiency in use of heat for cooking but still rely on fuelwood, charcoal, or biomass. Let’s be clear: there is nothing improved in continued suffering. No woman in Africa should have to cook again with fuelwood, charcoal, and biomass.”

African leaders also emphasised the need to build clean energy self-sufficiency across the continent, both in terms of supply, and infrastructure. This aspiration will help protect Africans from the high costs of importing fuels and price fluctuations, and recognises the enormous resources of energy available in Africa.

Financing, subsidy and taxation

The IEA has estimated that funding of US$ 4 billion/year is required to achieve the 2030 goal of universal access to clean cooking. Many speakers noted that this sum, a total of $24 billion over six years, is not large, and ‘within the means of the international community’. One of the explicit aims of the Summit was to secure funding pledges, and a sum of US$ 2.2 billion was committed during the meeting. Dr Birol emphasised that this was ‘new funding’, not re-cycled earlier pledges. The funds were from a wide range of actors, including governments, the African Development Bank, other development agencies and entities (including World Bank and the European Commission), and industry.

So, how would this funding, along with the additional finance needed and being sought, be deployed? The answers to this will become clearer over the coming months, not least through a process whereby the IEA, working in collaboration with SEforAll, will individually list all of the financial commitments on the Agency’s website, and follow these up to assess progress.

The Ghanaian Second Lady speaking about her country’s plans to scale up affordable access to LPG

So-called ‘blended’ finance, including concessional finance (an instrument through which public funds are made available to the private sector), was seen as an important component to ‘de-risk’ the necessary private sector investments in, for example, energy infrastructure and market development.

Affordability of clean cooking was, as might be expected, given a good deal of emphasis. Subsidies were thought to be vital for accelerating access to clean cooking in Africa. Various applications for subsidies included directly reducing the costs to the consumer to encourage transition, and to achieve price stability. Although the country policy was not mentioned by name, Cameroon has for a number of years used subsidy to maintain a degree of LPG price stability, although not to reduce the average cost of the fuel to the consumer.

There was a call for subsidy finance to be ‘technology neutral’, with a focus on the higher tiers of performance, but discussion of attitudes from funders and investors to supporting LPG access was largely avoided. The President of the Togolese Republic did raise this potentially controversial issue, however. He said that subsidy for fossil fuel (he was referring mainly to LPG in respect of cooking) was ‘difficult for national financial institutions, as well as … investors’, and went on to add that there was ‘a need for funds to adjust their criteria in order to be able to invest in LPG and other fossil alternatives that are much cleaner than biomass fuels’. This harks back to President Samia Suluhu Hassaan’s comment on the role of gas in a ‘just energy transition’.

A number of countries are already pressing ahead with some of these critical policies on affordability. Uganda is introducing a special ‘cooking tariff’ for electricity to support eCooking. On taxation, several countries plan to reduce, or have reduced, tax on importing and/or purchasing clean fuels and stoves, including for example the zero rating of VAT on LPG in Kenya.

How much can carbon finance deliver?

The Mimi Moto biomass pellet stove – an example of technology benefitting from carbon finance

Carbon finance was widely discussed, and there were two overriding messages. First, despite the efforts put into this source of funding, African countries have not yet benefitted at scale from carbon-finance. Second, there is a lot of concern, and some loss of trust, over the actual (and perceived) lack of reliability of the current carbon finance market, and there was a need for more careful and thorough assessment and monitoring of actual carbon reductions. One key outcome was the establishment, at the Summit, of a Collaborative Task Force with over forty organisations committed to increasing demand and delivering improved and harmonised methods for managing the carbon market in Africa.

It was unclear to what extent that a scalable carbon finance market can be created for LPG. Although there are a number of examples where carbon finance has been used successfully to fund transition to LPG, including in Sudan and in Pakistan, I was not aware that this topic, nor any clear substantive examples, were discussed at the Summit. This was unfortunate given the important role for LPG in IEA scenarios and country plans, and the quite intensive focus on carbon finance during the meeting.

In the follow-up report from the Summit, the IEA states that ‘carbon finance could fill over 20% of the clean energy investment gap in Africa by 2030’. This is an important contribution, but even if achieved, would still only address one-fifth of the resources needed. Furthermore, the extensive discussion of carbon finance for the clean cooking transition, given the limits on what this source has the potential to fund, can be contrasted with the relative lack of attention to finance for health improvement, or from other sectors that would benefit from clean, efficient and safe cooking energy and technologies.

Linkage with Action on Climate and the Environment

Supply of wood and charcoal for cooking is one of the major demands on forest reserves across Sub-Saharan Africa

The links between securing clean cooking and the protecting the environment, both in respect of protecting forest resources and reducing climate warming emissions, received a lot of attention. Cooking, globally, is estimated to contribute around 2% of global carbon emissions, on a par with aviation, and shipping.

COP 28 included a commitment by the African Development Bank Group to channel US$ 2 billion for clean cooking over a period of ten years, and it was stated that this issue would also be a priority on the COP 29 Agenda. UNFCCC Executive Secretary, Simon Stiell, noted the importance of including clean cooking in ‘nationally determined contributions’ (NDCs), and that this was not currently being done in all national climate plans. He assured the meeting that UNFCCC would seek this and ensure implementation is monitored.

The French Minister of State for Development and International Partnerships, Chrysoula Zacharopoulou, in making France’s pledge for funding, emphasised the opportunities for coordinated planning and policy, and increasing visibility, provided by the Paris Pact on People and the Planet which has the following four principles:

- No country should have to choose between fighting poverty and saving the planet

- Every country should have its own transition strategy

- More finance is needed for vulnerable economies

- Greater efficiency is needed from the international financial system

It will be interesting, and important, to follow how COP29 and the Paris Pact deliver on the Clean Cooking for Africa agenda.

Can this IEA initiative catalyse the action needed to deliver clean cooking for Africa?

The approach put forward, involving the three pillars (scaling up finance, making clean cooking a policy priority, and catalysing multi-stakeholder partnerships), along with the high-level commitment, initial funding with a process for follow-up, seem to offer the ingredients needed for much more rapid progress than achieved hitherto. A Summit Declaration endorsed by all key parties was produced, sets a strong tone, and carries plenty of ambition.

Countries that include Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia, have all endorsed the policy pledge and committed to adopt and implement ‘a suite of policies and regulations adapted to national circumstances, which support scaling up clean cooking and attracting new innovations, technologies, institutions, firms, and investments’. Sierra Leone, Rwanda, and Kenya have also committed to being among the first countries to establish high-level ‘Delivery Units’ for clean cooking, with support from the Clean Cooking Alliance.

A majority of school kitchens across Sub-Saharan Africa cook with biomass, exposing cooks, pupils and staff to high levels of pollution

But will these and other countries across Sub-Saharan Africa see clean cooking for the vast majority, if not all, of their people by 2030? That does seem very ambitious, though that is not to say that this target should not remain the gaol. But this will need to see implementation of the key policy proposals discussed at the Summit, including integration of clean cooking into other major policy areas, ensuring performance testing with labelling, and incorporating clean cooking in funding requests to development partners, multilateral development banks, climate funds, etc. There also needs to be support for a wide range of actors in countries, including for awareness raising in communities, and for public institutions such as schools, health facilities and prisons to adopt clean fuels.

Three aims were set for the Summit: raising the issue on the global agenda, mobilising financial commitments, and developing a roadmap of concrete actions. What can be said about progress against these so far?

Aim 1: Ensuring clean cooking is on the global agenda

Editorial from Le Monde, 16 May 2024, commenting on the IEA Summit on Clean Cooking for Africa

In respect of the global agenda, it is clear that countries and key actors are now taking the clean cooking issue more seriously. The topic will be on the agenda of COP-29, and no doubt in many other relevant fora. But if the response of the international media is anything to go by, there is still a lot of work to do in conveying the importance of clean cooking beyond the world represented in Paris, their colleagues and social media links.

I searched ‘mainstream’ media reporting over several days immediately after the Summit, and apart from an article and editorial in Le Monde (unsurprising given the location of the Summit, and the fact that President Emmanuel Macron hosted a special session for heads of state at the Elysée Palace), there was little else of note in major developed country media platforms.

The Global Times (Sierra Leone) reported President Bio’s address, the ‘Guardian’ in Nigeria and Tanzania (but not the UK Guardian) ran articles on the Summit, The Financial Times noted the financial commitment by TotalEnergies, BBC Sounds ‘Focus on Africa’ mentioned the conference but avoided reporting on the Summit, preferring to feature a story about an improved biomass (briquette) stove in Malawi, and there were articles in ‘Down to Earth’, and ‘Health Policy Watch’. There may have been other pieces I missed, but if so, they were certainly not prominent. The fact that the Guardian (UK/international) did not (and has not so far as I can determine) run anything on the Summit, an issue that links health, poverty, climate, environment, gender, and development for almost 1 billion of the world’s poorest people, is extraordinary [most recent search: 09 June 2024].

Aim 2: Securing finance

As regards the hoped-for financial commitments, US$ 2.2 billion of ‘new money’ was pledged, for periods ranging from 2 to 10 years. A substantial proportion of this total was pledged by industry, perhaps indicating a more optimistic view of investment potential by these crucial actors in the clean energy transition. This funding is undoubtedly an encouraging start, and may serve to encourage others who have been hesitant about committing to this cause. But is nevertheless relatively little against a goal of US$ 24 billion by 2030.

It is also very reassuring to see that the IEA, working with SEforAll, will establish a mechanism to assess how these, and hopefully additional, financial commitments are deployed over the next 12 months and beyond.

Aim 3: Concrete action and momentum

In terms of a roadmap and maintaining momentum, the Summit Declaration called for swift implementation and a follow-up mechanism. A number of specific partnership initiatives were announced, with the aims of achieving synergy across policy areas, increasing cooperation with industry, and more effective sharing of knowledge and experience. The African Energy Commission (a body of the African Union) announced that it would establish an African Clean Cooking Programme with the remit of advocacy and awareness raising, capacity development for manufacturing, regulation, etc., and mobilisation of finance.

Many other commitments were made by groups of participating organisations to work together to help secure clean cooking across all of the available fuels and technologies – LPG, eCooking, ethanol, biogas, and improved biomass. For example, GeCCO (the Global Electric Cooking Coalition), confirmed a COP28 pledge to ‘support transition into electric cooking for a significant (more than 10%) proportion of households and institutions in at least 10 countries by 2030.

Cooking ugali with an LPG ‘Meko’ stove in Mukuru District, Nairobi

This is an ambitious goal for eCooking. But with 46 countries and a population of nearly one billion without clean cooking, this would only serve the clean cooking needs of probably less than 5% of the Sub-Saharan African population currently without access by 2030.

This does emphasise why LPG, the most widely available clean fuel, needs to be prioritised for SDG7 at least to 2030, and beyond. Among those focused on joint action to increase LPG access, the Global LPG Partnership announced plans to raise $US 1 billion in cooperation with the African Refiners and Distribution Association, while the LPG industry body, the World Liquid Gas Association, announced the establishment of a ‘Cooking for Life Africa Task Force’, an industry-wide initiative designed to help achieve cooking with LPG across Africa for which a roadmap will be launched at COP29.

Are investors on the same page as African governments?

Finally, as a participant at the Summit, I felt there was still a degree of disconnect between what country leaders (and their representatives) are stating are their aspirations for a rapid clean cooking transition, and what developed countries and agencies are proposing and offering. For example, I did not once hear a developed country/agency representative say something like, “Country XXX has launched such and such policy for addressing the interlinked SDG goals around clean cooking, environment, gender and development, and this is how we propose to support the government and its partners in achieving these goals by 2030″, or something like this. That’s not to say this will not happen given the various commitments made, but being explicit about how country strategy can be supported will surely help identify the opportunities and barriers, and result in more rapid and efficient progress.

Apart from Presidents of Togolese Republic (‘subsidy for LPG is difficult …’ ) and Tanzania (‘the role of gas in a just energy transition…’), commitments from industry (e.g. TotalEnergies), the industry association (WLGA), and the Global LPG partnership, little was said directly addressing the vision expressed by African leaders, namely that this fuel is the key to securing clean cooking for Africa by 2030. It seems that there is still a need for more open discussion about what is required to meet the SDG7 target, and commitment to achieve it.

![Level of wealth and % of consumption-based Carbon dioxide emissions (2019) [From 'Climate Equality' (Oxfam 2023)]](https://nigelgbruce.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Wealth-and-climate-emissions_Oxfam_2019_300-dpi_PS_Crop_1920-px.jpg)

Level of wealth and % of consumption-based Carbon dioxide emissions (2019) [From ‘Climate Equality’ (Oxfam 2023)]

To this we should add recognition of Africa’s historically tiny contribution to the current climate crisis, and that ‘the richest 10 percent of the world’s population are responsible for 50% of the global total consumption-based carbon dioxide emissions’ (2019 data), according to “Climate Equality: A Planet for the 99%”.

One is entitled to ask whether the wealthy countries, or at least the well-off segments of their populations, are doing enough to ‘make space’ in the world’s 1.5 deg C carbon emissions ‘budget’ to allow Africa to achieve clean cooking by 2030, while still aiming for net zero cooking by 2050?

It seems fairly clear that they are not.

Good article and summary of the event for those who did not attend it. It would be important to have a debate on the source of US$ 24 billion needed by 2030. There is mention of concessional finance, which is a debt instrument. Many African countries are heavily indebted, and adding more public debt, however noble the agenda is, risks making life worse especially for the population that is targeted by clean cooking interventions. Furthermore it risks pushing the solutions out of their reach. It is a difficult but necessary conversation to be had. The same goes for subsidies.

Thanks for your positive feedback, and for raising this important issue around financing and debt. The whole area of sourcing and providing finance for the clean cooking energy transition is one we are following closely. Regarding ‘blended’ and ‘concessional’ finance, the IFC has this to say: ‘Blended finance solutions at IFC can be structured as debt, equity, risk-sharing, or guarantee products with different rates, tenor, security, or rank. Under select facilities, they can also be performance-based incentive structures. Solutions are tailored to address specific market barriers and failures and the requirements of donor partners.’ So, as I read it, this may involve debt for countries, but not necessarily, especially if aimed at reducing risk for investment by the private sector. I would be very interested to see more discussion of this.