The grave of poet Edward Thomas at Agny Cemetery, near Arras

In May 2016, I set off on a 3-week bike ride to explore the Western Front, pursuing a long-held ambition to find out more about the Great War of 1914-1918. I took my tent and sleeping bag with the intention of camping when the weather permitted, and cycled a total of 1,500 kilometres from the Belgian coast near Nieuport to the Swiss border. It turned out to be a remarkable and very memorable journey through landscape and history.

Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living, but the dead

Returning lightly dance

These words, written by the poet Edward Thomas in 1916 just months before he was posted to France and killed at the Battle of Arras in April 1917, have long captured my imagination about the tragedy of the Great War. This is the story of my road to France.

Planning my route

It was when I found a French IGN map of the ‘Grande Guerre’ (Great War) on a visit to the Somme Memorial at Thiepval in 2014, that I knew my route would follow closely the line along which the opposing armies dug in during October 1914. Following the German advance through Belgium, the Battle of the Frontiers, defeat of the German army at the First Battle of the Marne and subsequent retreat, and the Race to the Sea, this 800 kilometre line of trenches became known as the Western Front.

Sir Edwin Lutyens’ great memorial to the Missing of the Somme at Thiepval, with an installation ‘Shrouds of the Somme’, by Rob Heard that commemorates British and Commonwealth dead

How the Western Front came to lie along this line: main battles and army movements which determined the position of the front by late October 1914

The journey begins

I suppose that my ride really began as I cycled, full of anticipation at the prospect of what lay ahead, from my brother-in-law’s home in east London to Stratford Station, there to catch a train to Dover and then the ferry to Dunkirk. From the port, I rode along canals and through the fields of Flanders to Diksmuide, and then to Ypres, a city almost completely rebuilt from rubble and ashes. After a day exploring the Ypres Salient, including the German cemetery at Langemark and the infamous Passchendaele, I turned south through the battlefields of Artois, past the Canadian National Memorial at Vimy Ridge to reach mediaeval Arras, another city devastated by the war and beautifully restored.

The ‘Grieving Parents’ by Käthe Kollwitz, at Vladslo German Cemetery near Diksmuide, Belgium. The sculpture is the artist’s memorial to her son Peter, who was killed near Langemark in 1914

The Art Déco style Conservatoire de Musique et de Théâtre, in the heart of Saint-Quentin.

Riding south from Arras among the rolling chalk hills of Picardie, I explored the monuments, museums, railways and other reminders of the Battle of the Somme and the terrible loss of life that resulted.

Close to the River Somme, my route then took me behind the Hindenburg Line, the defensive works built by the Germans as they retreated early in 1917. This brought me to St-Quentin, where I found the impressive, restored basilica and stunning Art Deco architecture that is a legacy of post-war reconstruction during the 1920s.

Mutiny and the road to Verdun

Beyond Soissons, yet another ancient, front line cathedral city that was badly damaged and rebuilt, I visited the impressive Fort de Condé, which stood on a wooded hill overlooking the pretty valley of the Aisne. In the old fort I learned about the Séré de Rivières defensive system, lines of fortresses built by France following her defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. After an anxious night under canvas battered by heavy rain near Soupir, I climbed onto the ridge of the Chemin des Dames, scene of the disastrous 1917 Nivelle Offensive that sparked mutiny in the French army.

Leaving the hills behind for a while, I visited the great Cathedral of Notre-Dame at Reims. This Gothic masterpiece once saw the coronation of France’s kings, and has now been meticulously restored after the wartime shelling and fire which destroyed the roof, most of the 13th Century stained glass windows and many of the sculptures.

Stained glass windows by Marc Chagall in Notre-Dame de Reims, completed in 1974 and replacing some of those destroyed during the Great War

East of the city, I passed through vineyards of the Champagne region and then climbed into the Argonne Forest where I found evidence of the fierce but little-known battles that raged across these wooded hills during the first few years of the war. At Verdun, I wandered among the fortresses, memorials and cemeteries that told the story of one of the longest and bloodiest battles in history, where Germany’s Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn sought – unsuccessfully – to ‘bleed France white’.

Deep inside the Fort de Vaux at Verdun, where a small French garrison were besieged by German troops, finally surrendering when water supplies ran out

Deep inside the Fort de Vaux at Verdun, where a small French garrison were besieged by German troops, finally surrendering when water supplies ran out

The vast cemetery beside the Douaumont ossuary at Verdun, with more than 16,000 graves

The vast cemetery beside the Douaumont ossuary at Verdun, with more than 16,000 graves

Lorraine and the Vosges Mountains

A reconstructed trench on the forest walk at Kilometre Zero, the southern end of the Western Front on the Swiss border

Turning south-east, I headed as rapidly as my heavily-laden bike would allow across Lorraine towards my final goal of the Vosges mountains, along which ran the old border between France and the German Empire. The annexation of parts of Lorraine and most of Alsace following the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War led to considerable anger and calls for revenge in France during the years leading up to the Great War, a sentiment played upon by politicians and others with nationalistic views.

This is a region with a long, fascinating and battle-strewn history. It was part of the Germanic Frankish Kingdoms and later the Holy Roman Empire for the best part of a thousand years. Alsace saw invasions by the French under Louis XIII during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), followed by Louis XIV later in the 17th Century and Napoleon in the early 19th Century. The Duchy of Lorraine (still within the Holy Roman Empire) passed to France in 1766 on the death of the Duke, Stanislas Leszczynski, by virtue of the marriage of his daughter Maria to King Louis XV.

During the Great War, in late 1914, Lorraine was the setting for a number of important battles including Flirey, Trouée de Charmes and the Grand Couronné. These engagements between the French and German armies altered the course of the war, yet are nowadays rarely spoken of.

As I reached the mountains, the weather broke. My route took me up onto the ridge above at the Col de Bonhomme and along the Route des Crêtes, the old military road built by the French in 1915 to supply the front line. In a howling gale with rain whipping up the steep hillsides from the south-west and over the road, I had to fight to keep my bike upright as I rode over the Grand Ballon at an altitude of 1,400 metres.

It was an experience that served to remind me of the terrible conditions endured by the soldiers, which – especially during the long, cold winters – were far worse than anything I rode through.

I passed by the battlefield of Le Linge as my progress that day was severely hampered by the storm, but did visit the peaceful sanctuary at Hartmannswillerkopf before descending through the famous Rangen vineyards to reach Thann. Gentler cycling took me south through pretty villages of pastel-coloured timber frame houses to the Swiss border. Here, at the aptly named ‘Kilometre Zero’, the Western Front ends among restored trenches and bunkers beside a small stream in the woods.

Remembrance and reconciliation

Beyond the adventure of cycling, and the opportunities to learn about Great War history, this was a journey of remembrance and a chance to reflect on my own reactions to the loss of so many young lives. In addition to memorials and ceremonies such as the solemn sounding of the Last Post at the Menin Gate in Ypres every evening of the year at 8 pm, I found countless other moments and places to remember. These ranged from the deeply moving Christmas Truce sculpture at Messines to the many small, lonely cemeteries on quiet lanes and beside farm tracks in the fields.

The Great War Christmas Truce memorial at Messines, Belgium. The sculpture was designed by Andrew Edwards and cast at the Castle Fine Arts Foundry, Powys, Wales

Just as important as remembrance are the examples of reconciliation and striving for peace that are to be found all along the Western Front. Again, these include some of great, international consequence, such as at Reims, where a plaque lying just outside the western entrance of the cathedral recalls the historic 1962 meeting between General de Gaulle and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. And inside the church are the remarkable stained glass windows commissioned from the German artist Imi Knoebel for the 800 year Anniversary. But I found many smaller signs of that desire for friendship and co-operation across Europe that has been one important legacy of the Great War, despite (or perhaps partly because of) the horrors of the WW2.

There is so much to discover along the Western Front. To help convey the extent and variety awaiting the visitor, I have created maps of each day of my ride to identify some of the most interesting and impressive sites on – or close to – my route. There are, for example, some of the best museums I have ever seen, and these help the visitor understand how the conflict came about, the weaponry and course of the war, and the impacts on soldiers, civilians and communities. Perhaps most interesting of all, they show how the Great War influenced and stimulated change across so many spheres of our contemporary lives, including social policy, political systems, technology, and medicine that are still so evident today, especially in Europe.

One of my day-ride maps, showing my route (the red dashed line) from Albert to Seraucourt-le-Grand passing through Péronne with its excellent ‘Historial de la Grande Guerre’ museum, and St-Quentin with its fabulous Art Deco buildings dating from reconstruction in the 1920s (full legend available)

A French radio set displayed at the Verdun Memorial Museum

Family and other stories

Visiting the Western Front was an opportunity, as has been the case for many, to look into family involvement and fortunes during the war. One close relative, Amédée Tardieu (my wife’s grandfather), was a French artillery officer. He wrote a fascinating memoir with accounts that range from those quirky and charming moments that happen even during a war, to some truly terrifying experiences under shellfire.

Amédée survived, but his younger brother Edmond did not. He was killed at the Battle of Malmaison on the Chemin des Dames in October 1917; we believe by a shell fragment. I set out to find his grave at a military cemetery in the Aisne Valley, and have since taken other family members there. This shared experience has given us some recognition of the life of this young man who was all but lost to memory.

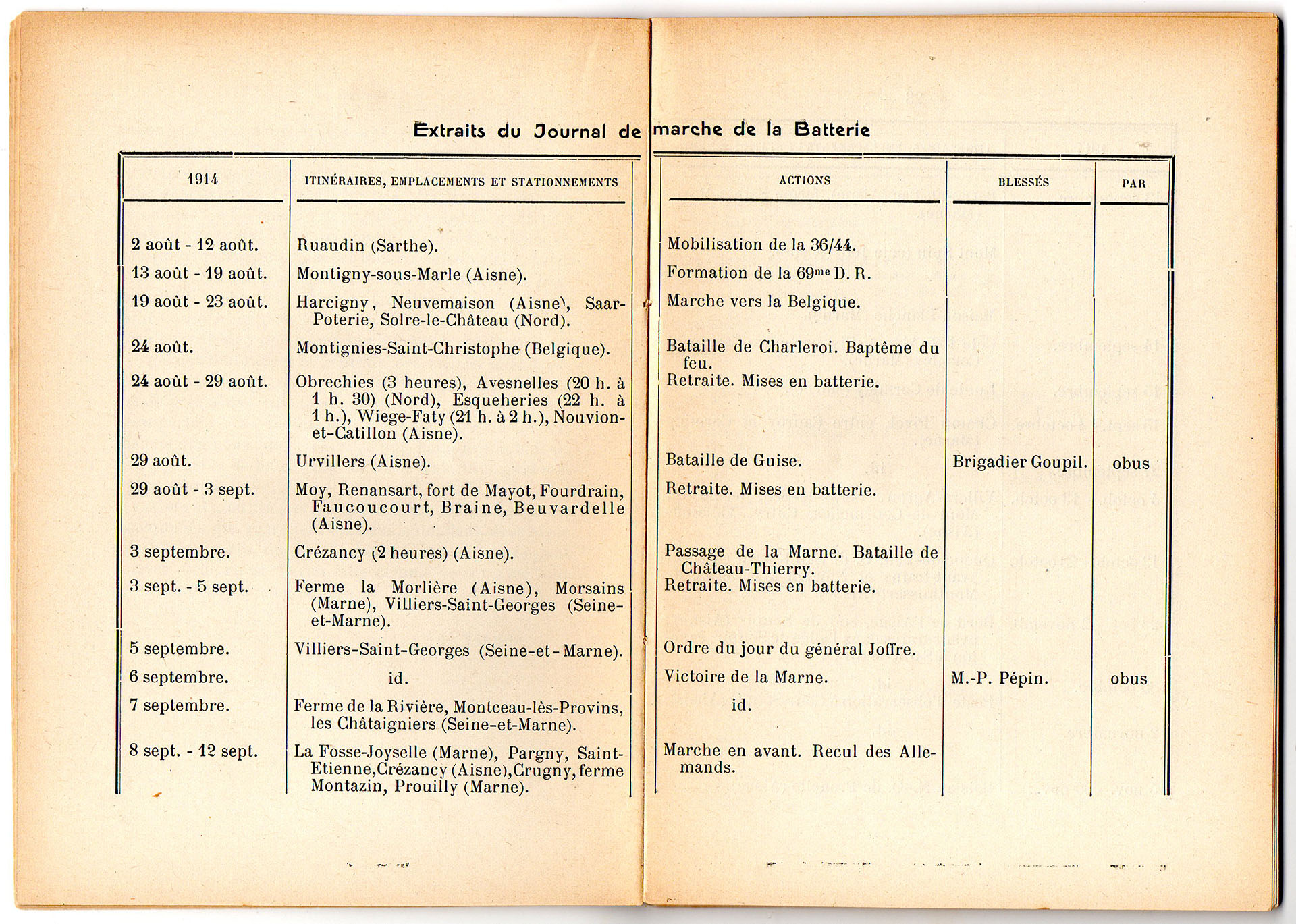

Extract from the Battery Journal kept by Amédée Tardieu recording their movements and locations, actions, injuries and deaths along with causes such as ‘obus’ (shell)

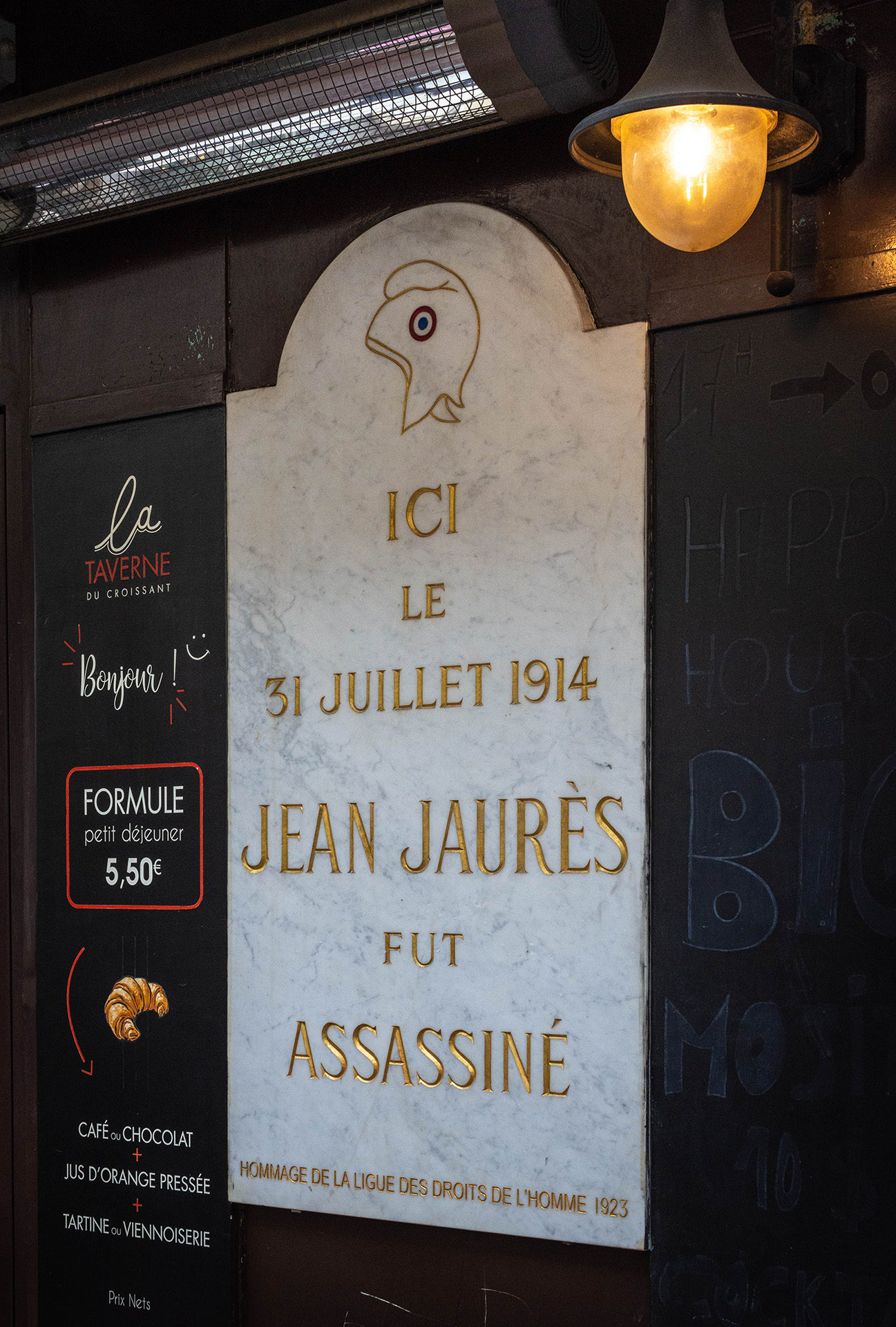

The plaque commemorating the assassination of Jean Jaurès outside the Taverne du Croissant, Rue du Montmartre, Paris

The ride stimulated my interest in the history of the Great War, and especially the events that led up to the outbreak of conflict in August 1914. Among the histories I have read are Christopher Clark’s ‘The Sleepwalkers – How Europe went to war in 1914’, Sean McMeekin’s ‘July 1914 – Countdown to War’ and ‘The Russian Origins of the First World War’, and Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Pity of War’. These have given me a lot of insight into this fascinating yet complex subject, although I know there are many other works, and other perspectives.

One story which really captured my imagination was that of Jean Jaurès, the great French socialist leader and pacifist, whose efforts to pull Europe back from the brink were held back by political scandal, then cut short by his assassination on the eve of war.

So, in 2019 I spent a couple of days in Paris, walking around the locations where the main characters acted out that drama, including: the Foreign Ministry (Quai d’Orsay), the offices of Le Figaro where the newspaper’s editor Gaston Calmette was killed by the wife of Jaurès’ key political ally Joseph Caillaux, the Taverne du Croissant where Jaurès was shot (and where I took my dinner), and finally the Panthéon where he is buried.

I have also read a number of narrative accounts of WW1, including ‘Storm of Steel’ by Ernst Jünger, widely acknowledged as one of the greatest books about the war. A year or so after my ride, I decided to take my bike again to the Somme and retrace Jünger’s steps as described in his book, to better understand the conflict from his perspective. So many young German men lost their lives, and while the German cemeteries and museums help us to remember that, out in the old battlefields I found myself having to work hard to keep this in mind.

The Town Hall at Bapaume, scene of a delayed action ‘acid bomb’ planted by the Germans as they retreated in early 1917, an event which killed a number of deputies attending a meeting and described in Ernst Jünger’s ‘Storm of Steel’

Recording the journey

The cycling (or walking), discovery, history, remembrance, and reconciliation are all parts of the story of a journey along the Western Front. Each of these will find a place in the book I am now writing, and which will be illustrated with photographs, drawings and maps. I’ll be posting progress updates on my website, with more short articles and blogs on the battlefields, memorials and most of all the people whose memory we must not let go of.

There are a number of organisations promoting opportunities for walking and cycling parts or all of the Western Front; these can easily be found by searching on the internet. The Western Front Way is a UK-based charity working closely with European partners and local communities to mark the 1,000 Kilometre route they have identified, and to promote knowledge, remembrance, and reflection. Their inspiration has been the recent discovery of a letter, written by 2nd Lieutenant Alexander Douglas Gillespie, shortly before he was himself killed, in which he proposed that the Western Front should become a path of pilgrimage.

“When peace comes, our government might combine with the French government to make one long avenue between the lines from the Vosges to the sea … I would make a fine broad road in the ‘No-Man’s Land’ between the lines, with paths for pilgrims on foot and plant trees for shade and fruit trees, so that the soil should not altogether be waste. Then I would like to send every man, woman and child in Western Europe on a pilgrimage along that Via Sacra so that they might think and learn what war means from the silent witnesses on either side.”

Linked articles

Exploring the Great War at Cannock Chase is a recent addition to my ‘Magic Rides’ series. It highlights some of the very interesting traces and memories of the Great War to be found in Staffordshire’s stunning Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Training camps, a the track of a military railway, old rifle ranges, and two cemeteries – one CWGC and the other for German Nationals – tell the fascinating story of Cannock Chase during the 1918-14 War. Among the links to the Western Front is how members of the New Zealand Rifle Battalion were brought over to Cannock to contribute their recent experience of evolving trench warfare from the sucessful assault at Messines in the training of new recruits. J.R.R. Tolkien was posted there during the war, and several of the most beautiful locations in the Chase are thought to have inspired some of the magical settings in Lord of the Rings.

Get in touch

Please do leave a comment (below), or get in contact if you have your own experiences to share, or would like to know more about my ride and progress with my writing project.

All photographs, artwork and maps (created in MapMaker 4 software) : © Nigel Bruce

Excellent piece, lots of interesting facts weaved into fascinating cycling experience. You can only get this well informed by walking (cycling) in the footsteps of those that experienced the trauma of war first hand. Great photos, maps and artwork. looking forward to reading more.

Thanks very much, and I’ll keep you posted with progress!

Hi Nigel, just wondering how you coped with a heavy laden bike going down some of the steep descents that are on this route?

Thanks for this – I am writing up a bit about the practical aspects of the cycling. For those interested, I can send you a bit more information. To answer your specific question: My bike was a Genesis Croix de Fer, with TRD HyRd cable/hydraulic disc brakes. I kept the baggage and panniers quite well balanced, and never had any problems with descending steep hills, even in rain. I did however ride the Route des Crêtes in the Vosges in a storm, with very strong, gusting cross winds. That was a battle, to be honest, but these were unusually difficult conditions. Even so, descending and braking was no problem, at least not when sheltered from the wind! I hope this answers your question. I’ll post this response next week. Are you planning to ride the Western Front, or do you have another trip in mind?

Delighted to find this website and really looking forward to reading the book Nigel. I am planning to cycle the Western Front Way next July. When will the book be published?

Thanks – All the best for your WFW ride, and don’t hesitate to ask if you have any questions about my trip. As to the book – I am at the stage of tidying up material to submit to a publisher, so if all goes well, hopefully it should see the light of day sometime next year, maybe mid-year/autumn. In the meantime, I’ll be happy to share some (draft) material with you if you are interested, for example for certain sections/battlefield areas, etc.

Thanks Nigel. I will do my research firstly and revert with any questions.

Great, thanks – looking forward to hearing from you in due course.

Thank you Nigel for that great information. I plan on cycling this route in May 2023 and I would like to know if there are any groups that would organise transfer of luggage and book accommodation on the route. That way I can enjoy each day.

Hi Marguerite, many thanks for this comment and question. First, all the best for your trip, and I’d love to know more about your plans for this if you wish to share, as in the route, time you plan for the journey, etc. As I carried all my luggage on my bike (in panniers), I did not look into the luggage transfer options. I have used these elsehwere in France (e.g. on a hike along the GR70 Stevenson Trail in the Cevennes) and just searched and booked on line. Good luck! Nigel

As a keen cyclist and motorcycle rider I was wondering if this route is accessible on a motorcycle?

The short answer is yes, definitely. My route was by road/touring bike, and all on roads, mostly minor but in good condition. There are a few sites (i.e. memorials, small cemeteries, bunkers, etc.) on farm/gravel tracks, but if you did want to visit these, I’m sure you would be OK on a motor bike. If you want to explore the Kilometre Zero forest trail (near Pfetterhouse, on the Swiss border), you would have to walk that. Happy to provide more information if I can be of assistance.

Hi Nigel, just searching in Facebook found your webpage and this reportage about the western front. I have holidays in may and planning to do it, starting in Switzerland. I had the gpx from the western front way UK, but somehow my garmin didn’t processed well last year and had to change on the road plans, but this time I will ride that route. Thanks so much for your blog, pictures and infos!Motivated me even more to do it.I will ride my beloved bike Leo with all the gear to camp on route. Thanks again and Ill keep reading your blog. Oh, happy new year by the way…always forget is a new year already.Sorry all misspellingand gramma mistakes, I speak spanish actually.

Hi, great to hear from you, and thanks for the interest. All I can say (again) is that it’s a brilliant ride, and so interesting. What type of bike is your beloved Leo? Willl you bee keeping a blog – and if so, where/how? All the best Happy New Year, and do keep in touch.

Hi Nigel, Thanks for your answer.I usually just do pictures to send home where am I at the moment. I live in Switzerland and my mom is in Panama(where I come from). I hope this time my garmin works better and now I have to take time to look at the map and put my plan together, work has beeing stressful, but have to make time. Thanks again and yes, we will keep in touch! Greets Denise

Hi Nigel!

I loved reading your article about your journey. I am doing a similar route this April and I am planning out the route now. Do you have those day maps you plotted for your route available? They look super helpful. Again thank you!

Best,

Matthew

Hi Matt, many thanks for getting in contact, and all the best for your trip in April. I’ll reply to your email address re sharing the maps.

Hi Nigel,

Thank you for the wonderful account of your trip. I am about to start planning – intention to pay respects at Menin Gate to Great Great Uncle obliterated at Messine, and survey the Somme where another ancestor fought (and survived with a “GSW left buttock”). Will be using my trusty Cannondale Synapse (possibly bit too much of a road bike for the task? Not that getting an alternative is really an option). I would be grateful to see your route maps to get me out to speed?

Best wishes Simon

Hi Simon, thanks very much for your comments and enquiry about my route maps. I’ll write to you via your email separately, and we can discuss your provisional route, etc., and I can share relevant maps. Best wishes, Nigel

This comment is very late, but thanks to Nigel, I had a wonderful ride last Spring. Nigels descriptions of the route and the locations helped me immensely as I came from the United States, and hadn’t been to the area before. The scenery was unbelievable and I was so glad to have specific locations to ride past, like Lochnagar Crater, Theipeval, and Vimy Ridge among others.

Cheers Nigel, thanks so much!